Description

In 2016, Boston-based Ethiopian group Debo Band released Ere Gobez, their second and, for now, final LP. The band played a handful of festival dates over the next few years, gradually trailing off into silence. DA Mekonnen, founding member and bandleader, has spent the years since then slowing down. He questioned nearly every foundational element in his life. He got sober, dove deep into film photography, ecology, and astrology, and focused on feeling the deep and difficult feelings contemporary reality gives us so many ways to escape. He also built a solitary music practice from scratch, which he refers to as an “ancestral practice” – a connection to a spirit of independence he traces back through his family. The idea of an ancestral practice is also a nod to his grandmothers, who were each spirit workers involved in zār, a kind of ritual to purge spirit possession with roots in Ethiopia. Mekonnen’s goal in the reset was to “make things with the kind of love you can’t ever take back,” to quote from Jarod K. Anderson, a poet and writer who goes by The Cryptonaturalist and whose work is one of many inspirations behind Mekonnen’s new project, dragonchild.

dragonchild takes the exploration of Ethiopian music Mekonnen began with Debo Band and explodes it into vivid, three-dimensional space. Where Debo called back to the sounds of 1970s Addis and added original material along those same lines, dragonchild shatters traditions and boundaries, incorporating sampled material, field recordings, experiments in high and low fidelity, and the throughline that unites the diverse sounds, layers of Mekonnen’s rich and ecstatic saxophone. “I’ve been thinking a lot about ego death and being willing to let certain things go,” he says. “Things that made you feel good about yourself, made you feel really successful. I think artistically those things can be really dangerous. They can be dangerous crutches.” In moving beyond what brought him success in a fickle industry, he is braving new territory to bring us something more, something vulnerable and alive.

The name of the project derives from

Haile Gerima’s 2008 film

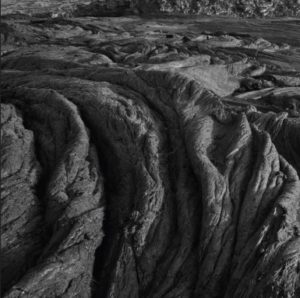

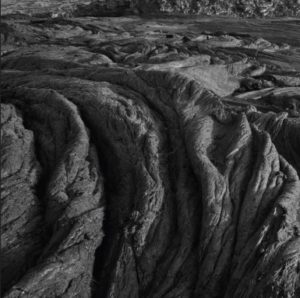

Teza, the story of an Ethiopian lab researcher who returns to his small village after long sojourns in both Germany and Addis Ababa. Near the end of the film, there is the hopeful but enigmatic line “do not despair – we are children of the dragon,” which evokes the resilience of the people and of the earth. It’s a nod to Erta Ale, the active lava lake in Ethiopia photographed by

Michael Tsegaye for his

Afar series, included as part of the album artwork and recognized instinctively by Mekonnen as “portraits of the dragon.”

Although the seeds of this music were solitary, collaborations abound in the

dragonchild universe, with artists as diverse as ambient producer

claire rousay, the Addis Ababa based multi-instrumentalist

Ethiopian Records, and percussionist

Sunken Cages. These duets fly freely across the borders of genre, stretching out like long late-night conversations between close friends, work created as an expression of community, abundance, and freedom.

The physical form of the record is an eight channel, four LP mix of the final track and centerpiece of the album, a twenty-minute-long saxophone meditation. It is no coincidence that this mix is impossible to listen to alone. In order to experience it fully, you will need three friends and four turntables.

The photograph that occupies the front cover, also taken by Michael Tsegaye, is of another photo, one placed under glass in a cemetery as part of a common practice in Addis Ababa. Over time, water damage cracked and weathered the glass, and at first what you see are the sharp and irregular fractures, rendered with extreme clarity. It is only on second glance that you see the true subject of the portrait, the ghostly ancestor gazing out from the past. “We have to fight for our lives,” Mekonnen says. “That’s the thing that I feel most adamant about. Our creativity is our birthright.” With dragonchild, he gives voice to a new sound, hundreds of years of Ethiopian and American music all resonating at once. “The record feels and breathes to me like the Ethiopian music I’ve been trying to figure out my whole life.”